In my internet trawling I found a nice article by Roland Kraft on Ken Shindos early work, in particular the Cantabile amplifier from back in the day. It was on a German site called LowBeats.

Early work by Japanese tube guru Ken Shindo

Roland Kraft August 19, 2015

Its components were as unique as the person Ken Shindo himself: the company founder, developer and sound visionary died in 2014, creating a multitude of addictive and benchmark-setting sound machines in 35 years. Ken Shindo and his employees in the Shindo Laboratory not only built an enormous number of tube amplifiers (as well as loudspeakers and turntables), but also a large number of designs with very different tube configurations.

However, the Japanese tube and vinyl specialist never made a religion out of a certain operating mode (e.g. push-pull or single-ended), nor did he do the same with certain types of tubes. However, we are not aware of any OTL (Output Transformer-less) amplifiers from Ken.

Shindo connoisseurs know that transformers of all kinds, including many historical variants (he also liked to use old transformers from Triad or Western Electric), were his trademark. Decades ago, the Japanese manufactured preamplifiers with output and input transformers, for example, which in this country in terms of hi-fi – unlike in the older German studio technology – was long considered an absurdity.

Ken Shindo’s early products were still strongly influenced by his intensive involvement with American audio engineering and the high-quality US consumer electronics that were built in the USA up until the early 1970s. In this regard, people in the USA like to speak, and rightly so, of the “golden” era, in which particularly complex devices were created; such as the legendary audio components from Marantz, McIntosh or Scott.

During the 1970s and 1980s, little was known outside of Japan with what enthusiasm Japanese hi-fi fans, tube fans and collectors of old studio technology had thrown themselves at once top-class US brand products. And the meticulousness with which not so few Japanese freaks had scraped together large collections of antique US cinema and sound reinforcement technology (keyword: Western Electric) was only noticed by the dismayed Americans when the market was almost empty. Nowadays, this former “scrap” is traded in the price range of luxury cars.

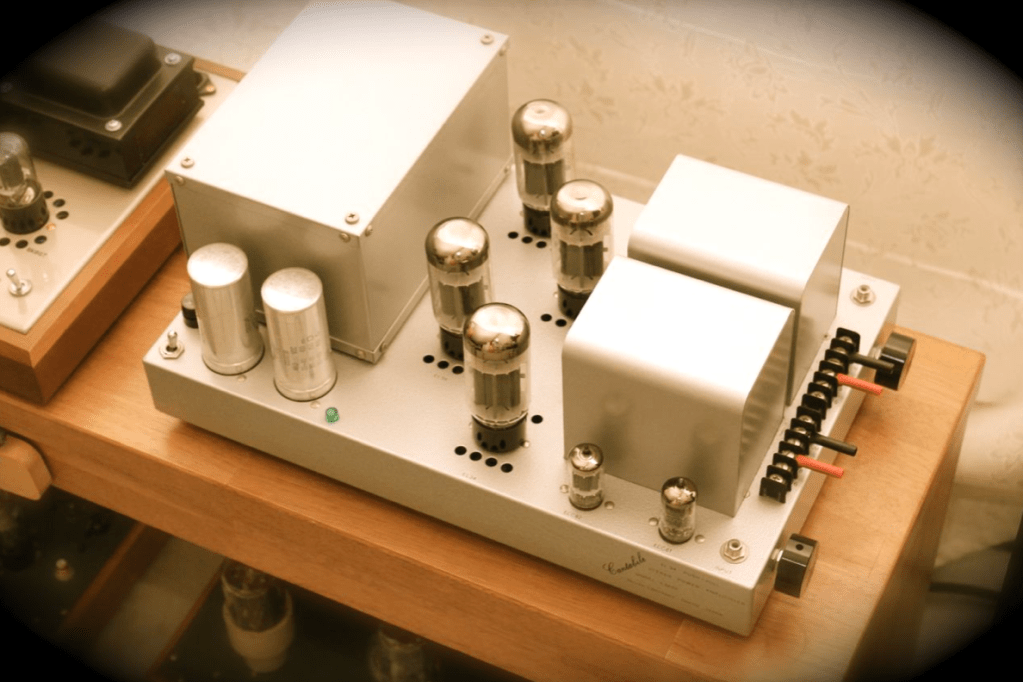

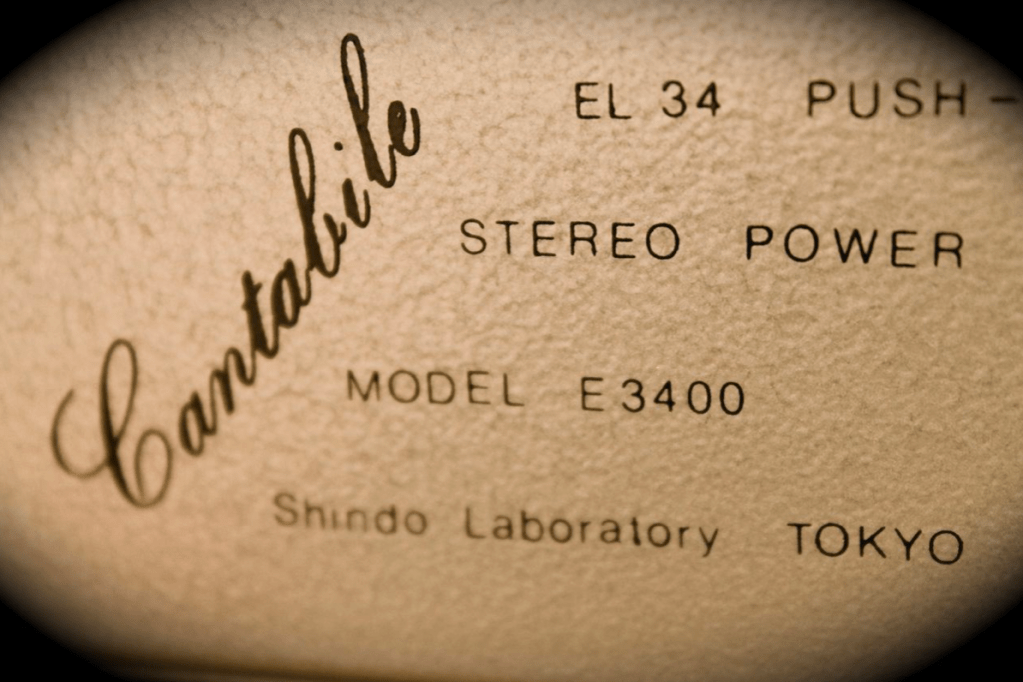

An early Ken Shindo work, not yet painted green. But back to Ken Shindo and his Cantabile, which, in contrast to the Shindo amplifiers later exclusively painted green, still came in a silver colour similar to a hammer blow. The Cantabile is a push-pull power amp design featuring the EL34 that was released sometime between 1982 and 1985.

How long the Cantabile was offered can no longer be determined. It is not even possible to find out more about Ken Shindo’s son Takashi Shindo, since the master craftsman worked together with very few employees who only manufactured individual assemblies and left hardly any notes.

The price at that time within Japan can no longer be reconstructed either; As a rule of thumb, a good used example of the Cantabile should cost a high four-digit amount in euros these days.

An ECC81 is used as input and voltage amplifier in the Cantabile, while an ECC82 serves as the driver stage. The total of four double triodes have been consistently switched channel-separated, and the input level controls are located behind the two cinch sockets.

Cantabile in all its glory. The transformers are located under the two smaller covers (Photo: R. Kraft)

In Japan (even today) power amplifiers without input level controls are not common; with us, this practical feature mostly fell victim to misunderstood purism. It is therefore a matter of interpretation whether the Cantabile is an integrated amplifier with one input – which works wonderfully with sources that are not too high-impedance – or a power amplifier 🙂

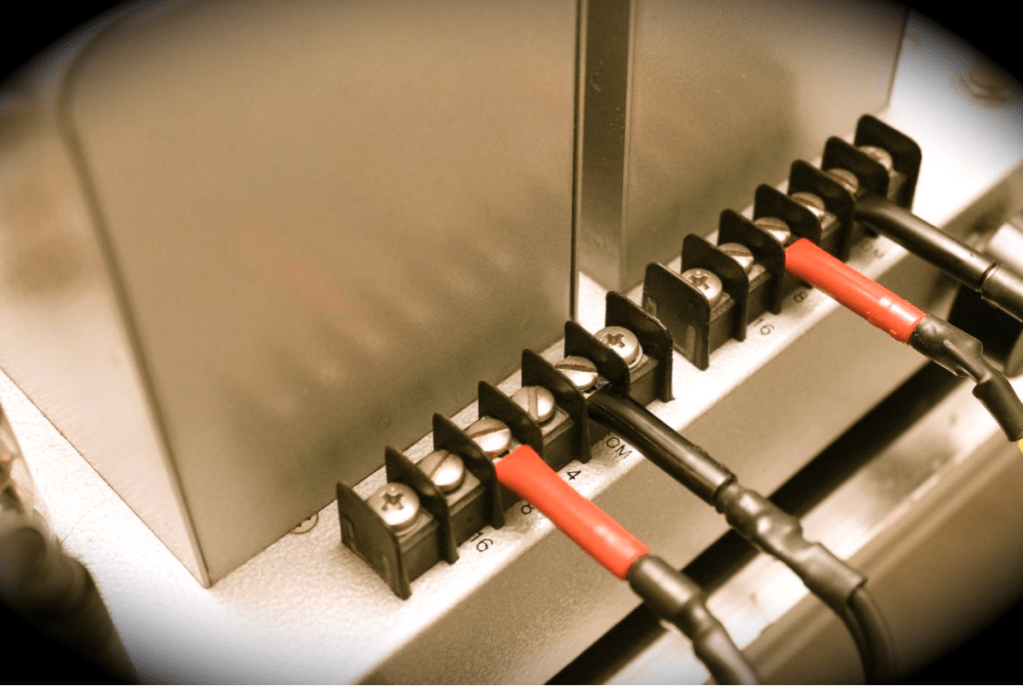

One could also regret the Cantabile’s practical, stable and, in particular, contact-safe speaker screw connections – they are located directly on the two output transformers. And of course, in addition to four and eight ohm connections, the power amp also has 16 ohm taps on the output transformers, a homage to vintage collectors who use historical loudspeakers.

All of the amplifier’s transformers reside under sheet metal hoods, with Shindo arranging the four output tubes in between in a somewhat unorthodox manner, namely they are offset on imaginary 45-degree lines. The reason for this is obvious: the EL34 should not heat up one another if possible.

What else is noticeable on the 43 by 28 centimetre Cantabile chassis are two thick capacitors, which are responsible for the hum filtering in the power supply. Completely different from what is usual today, these are so-called multiple electrolytic capacitors, which are several capacities with a common minus connection. Nobody really knows why this very useful old electrolytic capacitor design is frowned upon these days…

Classic old-style multiple Electrolytic capacitors. (Photo R. Kraft)

Loudspeaker connection: screw terminals (Photo: R. Kraft)

Shindo: Components from the USA

A look under the chassis of the 100-volt device reveals that almost all of the electronic components used come from the USA, or to be more precise, from exactly the same sources from which the aforementioned American heyday components “nourished”.

Quite apart from the fact that one can rightly be amazed at the lifespan of the material used, the circuitry of the Cantabile is obviously a rather complex piece of amplifier with a powerful power supply. As usual with the Japanese, it already has a filter coil that is screwed under the transformer cover.

In addition, a transistor (!) was later added, a so-called gyrator circuit, which electronically simulates a filter coil; a technique that could later be found again in various Shindo devices. Ken Shindo seems to have not only restored many of his older creations (when he got them back on the workbench), but also retrofitted them.

Proper but generously laid internal wiring is also one of Shindo’s trademarks, as is the use of long-life Mallory and Sprague capacitors. No less striking are the thick carbon mass resistors from Allen-Bradley and the filigree art of soldering using solder lugs.

However, the use of circuit boards, as in this case, is rather an exception in the Shindo Laboratory. And that the use of cathode bypass electrolytic capacitors certainly does not have to be regarded as a sound brake has already been proven in many exceptionally good Shindo amps – even if component purists now groan in horror…

Given the age of the device, the sound impression of this tube amplifier can only be astounding. The outstanding, but, as we will see in a moment, superficial diagnosis is that the Cantabile can not only easily keep up today, but can even inspire in the long term. The EL34 power amp is neither a performance giant nor a bass monster.

Reproducing tendentially to be slim and fast rather than voluminous, Shindo’s design spans a huge, enormously deep and wide sound stage that actually conveys the impression of “air” and a three-dimensional structure.

This, yes, “simulation” of an almost tangible room, which makes the walls of the listening room disappear as if by magic, is very, very impressive, but not even the decisive factor in the sound of this amplifier, which – unfortunately – also proves that, at least in terms of tubes, modern designs have not brought any real progress beyond bandwidth and control.

Shindo Cantabile: Wiring (Photo: R. Kraft)

An excursus: the interface to the listener

As is always the case with Ken Shindo’s creations, it is also true in this case that neither rather flat hi-fi terms (spatiality, definition, transparency, dynamics) nor objective statements (e.g. distortion or freedom from interference voltage) really make a decisive contribution to the sound perception, but something completely different .

Namely the state of mind of the listener, or the way in which reproduced music actually affects the listener. There is no objectifiable benchmark for this effect, and the usual hi-fi criteria – in themselves only a clumsy substitute for the way of describing the listener’s condition – hardly apply.

The interface between the installation and the listener is usually also strongly influenced by subjectivity and expectations.

These expectations can also be influenced by bias, the kind of bias that arises from the sometimes compulsive attempt to translate technical principles that are considered generally valid into a sonic result or to correlate them with the sound.

Which should actually make the pure technicians, who usually completely ignore the other side, sit up and take notice. But their reaction should usually be limited to researching hearing curves, measuring distortion and pouring the said condition into tables, formulas or reproducible principles.

That’s just how science works, that’s how it has to work in order to get us further and ultimately every (tube) amplifier works according to such rules so that it works at all.

If it were otherwise, you could also pour beads or Schuessler salts into a pot with water, attach connections and connect the construct to speakers …

However, classic amplifier construction often fails at the interface to the listener, more precisely, at an exact, reproducible description of the listener’s state of mind.

A statement that many hi-fi fans would naturally not subscribe to. Because a device built according to all applicable rules of technology, which also meets or even exceeds the usual metrological requirements, is considered “unassailable”, especially with a purely electronic approach according to the current state of the art. Such an amp is never “bad” because it simply cannot and must not be.

Then, as usual, the circumstances should be considered in a differentiated manner, other excuses – and that’s what it’s all about – are possibly cables, “unsuitable” speakers, the acoustics, “bad” electricity or the wrong rack.

If it were purely based on theory, the technology was so mature a long time ago that further development is ultimately limited to the crazy people from the high-end corner who simply do not want to see that a modern amplifier chip could do anything but the zeros behind the comma mean nothing, cannot be the last word.

All sound descriptions of hi-fi components are only a more or less crutchy attempt to describe what the transmission of music triggers emotionally in the listener.

However, the frequently used linguistic methods are clumsy, sometimes exaggerated, miss the point or are part of the necessary repertoire of authors who try to convey their message somehow and thus ultimately express whether an amplifier has managed to make the message “reach” the listener.

Can we really accommodate a symphony orchestra in our living room using a (stereo) system? Can we recreate the atmosphere and dynamics of a rock concert? Let a grand piano sound behind the loudspeakers? Experience an opera “live”?

Unfortunately, the answer to these questions still has to be a no, characterised by modesty and realism, even if the opposite is often claimed and even if a so-called “top installation” is in a huge room and has loudspeakers that are too “big”. Figure are able.

The expression “live”, used in some connection with the current tools of music reproduction, is probably one of the most inappropriate crutches in the word bank of trying to ennoble and sometimes necessarily counting peas (hi-fi) authors, who sometimes have to recognise over their still steaming pile of letters, that they could only describe half of one component because there was simply nothing to “feel” about the second half, which was at least as important.

Incidentally, ironically, this form of capital failure tends to affect super-expensive monster devices or so-called “ultra-high-end” systems…

The Ken Shindo Effect

This – sorry – somewhat lengthy insertion into the Cantabile story should only serve to explain the “Ken Shindo Effect”. It is precisely he who is the deeper reason why the equipment of the deceased old master enjoys such cult status.

The impossibility of reproducing the real event and one’s own experience despite the greatest effort must lead to the conclusion that (hi-fi) reproduction is possibly just an art form in its own right, i.e. actually just another interpretation.

Where one shouldn’t chase ideals that are impossible to achieve, but rather concentrate on conveying between the lines a much more important piece of information in the midst of a stylishly written message. And that’s exactly what Ken Shindo was able to do with his devices.

He knew how to modulate this interface to the listener in a masterly way, in that his amplifiers even roughly modulated different tonal characters – or listener needs? – represent and still be able to trigger the deepest satisfaction.

Good old Cantabile can do that too. She captivates her listener, engages him and conveys the essence of music (any kind). The magic that this final stage exerts is difficult to describe or grasp. But he works.

It can be assumed that the Cantabile was created between 1982 and 1985 (Photo: R. Kraft)

So, is it worth looking into the used market for Ken Shindo’s Cantabile? The answer: a sad yes, of course!

It’s sad, because outside of Japan hardly more than three or four Shindo creations appear used every year, which are usually offered for horrendous sums, but were often tinkered with by know-it-alls.

If you’re lucky and can buy a Shindo amp, perfect technical support or restoration is actually only possible in the Shindo laboratory: http://www.shindo-laboratory.co.jp

You must be logged in to post a comment.