All of these Japanese exotica brands have a certain mysticism about them; Shindo, Kondo, Sakuma etc. They all have very deliberate and defined philosophies around their approach to design.

In the Kondo world:

“Silver is the centre of our sound creation. Sound of silver is the warmest. It can also express music with fully liveliness and sharpness.

In Audio Note, the most importance of using silver is to truly reproduce music.”

From the Kondo website:

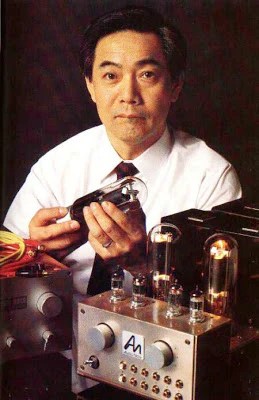

“People call Audio Note’s founder Mr. Hiroyasu Kondo “the Audio Silversmith”.

Being the first person to use silver wires in audio designs, Mr. Kondo was given names of “The Audio Silversmith” and “The Master of Best Audio” for his position in the audio industry.

To get “the highest sound quality”, Mr. Kondo did comprehensive researches from the input position of audio signal up to the sound output, without a bit of compromise.

The charm of silver wires was brought up by his hands.

The sound of silver is warm yet vivid; it can fully express the vitality of music.

With bold but prudent idea to get the highest sound quality through using silver, an expensive metal which had never been used in audio design before, the sound character of Audio Note then was created. Audio Note silver wire is a product of audio passion with careful attentions on material handlings. And the products that applied Audio Note silver wire deliver sound qualities that reached and beyond the highest worldwide standard.

The products of Audio Note are made for and bond with audiophile’s heart. They seamlessly blend audio into music, with the ability of playback music with the best audio performances.

The Pioneer of silver audio – Kondo – Audio Note

The legend continues

After founder Mr. Kondo pass away, there is no change in Audio Note.

The philosophy of hand-making product set by set have no change.

The use of pure silver wires have no change.

Making transformer by the most skilful technician, making original silver capacitors, using direct wiring on all products.

All for the making of good sound quality.

To fulfil audiophile dreams. To be original. To make products reaching the realm of art.

It is the policy of Audio Note.”

I’ll upload or link to whatever interesting articles I can find about Kondo and his approach. Here is an article I found somewhere years ago, I lost the reference, but here it is anyway:

Kondo’s Thoughts on Hi-Fi

Music is a complex vibrating wave that interacts with everything it comes into contact with. Most modern electronics engineers would hardly agree with this approach; they first destroy the signal and then try to restore it. When passing through such an audio system, the music becomes disgusting, unrecognisable and coarse. And increasing the volume is unable to restore its beauty. Just as a bitter product can be sweetened with sugar, but not improved, so the lost information cannot be recreated in the original, no matter what the various theories of tonal “improvement” and error correction claim.

Hiroyasu Kondo

PARTICLES AND WAVE MOTION

The behaviour of sound waves cannot be explained using electrical theory alone. A huge number of factors influencing sound reproduction remain unexplored. The world of sound is much deeper than we can imagine.

Albert Einstein said that movement is energy. To me, movement is sound. I am even more convinced of this when I hear the mounting storm of sound in the middle of Wagner’s Tannhauser Overture. Especially in the last performance by the great maestro Toscanini on April 4, 1954, when the particles of sound seem to collide with each other and merge into a stormy whirlpool, rolling over the listener with the force of the elements. It seems to me that the particles of sound perform unimaginable iterations. I can clearly imagine how, overwhelmed by a wave of emotion, the 87-year-old maestro gave his whole soul, conducting at that farewell performance, and how, in response, the musicians put into their performance all the skill they were capable of.

Sound is supposed to travel in straight lines, like any waves. But this is true only in a wide, unobstructed space. In reality, the movement of sound waves is incomparably more complex, they collide with obstacles and with each other, and sometimes, forming vortices, they spread along indescribable trajectories. In my opinion, those who work with audio equipment need to have spatial imagination in order to clearly imagine visual images in their heads

MAJESTIC SOUND

Polymicrophone recording technology disrupts the harmony of the combination of sound waves.

Every morning at 5 o’clock in the main temple of Zen Buddhism, Soji-ji, 200 monks gather for prayer. On a wide space of a thousand tatami mats, the monks, seated to the left and right under the temple vaults, begin to quietly chant sutras. What a majestic sound! This ritual, unfailingly repeated day after day, brings a person to a state of nirvana. What must I do to express this majesty with the help of sound-reproducing equipment?

First of all, I must think about how to “collect” the sound. Modern recording methods usually involve arranging several microphones like pieces on a chessboard. However, I am skeptical about this method, mainly because the more microphones are installed, the more emphasised the sound near each of these microphones is perceived in relation to the others, but the most important thing is violated – the overall harmony of the combination of sound waves. Think of the sound of a twin-engine airplane: You will hear not two even tones, but a third, smoothly vibrating, sometimes rumbling sound, which is the result of a slight difference in the frequencies of each engine. Musical instruments and voices also necessarily generate this “difference” sound. It seems to me that it is these weak beats of tone that give birth to harmonics, merging into harmonies and chords, and as a result turn into a beautiful, exciting sound.

ANALOG SOUND – DIGITAL SOUND

Modern analog systems sound like digital. At first, such sound is stunning with its high resolution, but is it right?

An analog disk does not necessarily produce analog sound, and a digital disk does not necessarily produce digital sound. To me, audio systems on the market today sound digital, even at the level of their analog stages. Each note sounds so sharp and piercing, as if the signal were rectangular. It is like an image taken with a digital camera. The boundaries are extremely sharp and noticeable. At first, such a sound is almost stunning in its high resolution, which is, in fact, fragmentation. But is this really the royal road to audio?

I want a sound in which the individual particles of sound are interconnected. It is easy to get a “soft” sound from a conventional amplifier simply by choosing the right parts and circuitry, but such softness is actually a deception, since it means “blurring the boundaries” technology.

It so happened that 30 years ago, vacuum tubes produced a really soft and full-blooded sound. This situation still exists today. However, now, if any “improvements” are made to the sound, then one can say that digital colouring is simply added. I do not accept this tendency. I want to get a sound in which each of its individual parts, like the sun, would radiate energy into the surrounding space and at the same time they would merge into one. Ultimately, in my reasoning, I again need to return to the stage of sound recording.

THE SOUND OF ELECTRONS

Vacuum tubes designed for high efficiency have a heavy sound, while tubes of simple design sound transparent.

Have you ever seen electrons moving? The textbooks tell you that they are spinning around protons at breakneck speed. Sometimes I have a very clear visual image of electrons moving. I mean what is called thermionic emission. Vacuum tubes designed for high efficiency have a heavy sound, while simple tubes sound transparent. I think the reason for this difference lies in the ratio of the emission to the anode voltage. Thermionic emission produces an electron cloud around the cathode and the filament. The stronger the emission, the denser the cloud, the more electrons it contains. The essence of the tube’s work is to separate, like caviar, each of these electrons from the general mass and deliver them to the anode without loss. The efficiency of this process is directly related to the voltage applied to the anode.

Consider the design of a pentode: electrons are actively emitted by the cathode, forming a very dense cloud. While the first control grid with a fine-mesh structure, located very close to the cathode, holds the bulk of the electrons very close to the cathode, some of the free electrons “indecisively” rush between the grid and other electrodes of the tube, which have a negative potential. It seems to me that all this fuss somehow affects the character of the pentode sound. How then to reduce the number of these “aimlessly” hovering electrons? Having weighed all the “pros” and “cons” there is nothing left but to agree that the control grid should have a large-mesh structure, and the anode voltage should be increased. Directly heated triodes meet all these conditions. But here a new problem arises: the filament, which is also the cathode, is more susceptible to vibrations, and in turn, these vibrations are transmitted to the electrons, which again affects the sound … What a difficult thing – audio equipment.

SOUND OF A TRANSFORMER

The main factor determining the sound quality of transformers is the materials from which the core and windings are made.

Those who have studied electricity have only a superficial knowledge of what a transformer is, because the schools only cover power transformers. Sound engineers have to rely on specialised publications, but even they pay little attention to transformers. Does this mean that the transformer is a relic of the past? Certainly, the transformer has a number of problems inherent only to it, such as m-linearity of the magnetic core, excitation distortion, Barkhausen noise. Fastidious theorists cannot stand these problems, and engineers who care only about the profitability of products try to do without transformers altogether and design cascades containing only resistors and capacitors. Transformers have been banished from circuit design. I consider this a mistake and am sure that a high-quality transformer can sound great. I can give many examples of this. For example, at a radio station, the audio signal passes from the input to the output through dozens of transformers. If the transformer were the root of all evil, the sound of TV and FM broadcasts would be simply unbearable. However, it is not that bad. What is the matter then? I want to answer this question.

I am very interested in how the quality of sound changes when passing through a transformer. A transformer can be thought of as a high-pass and low-pass filter, which explains why audio engineers tried to make the bandwidth of transformers as wide as possible. Personally, I am still afraid to leave mains transformers on for long periods of time, because I well remember how old transformers overheated, which often led to fires. Yes, it was quite a challenge to make a good transformer from second-rate iron and cheap wire.

As a result of numerous experiments with various transformers, I can divide their quality into two categories – soft-sounding and hard-sounding. The main factor determining the sound quality of transformers is the materials from which the core and windings are made. Let’s look at the core first. Permalloy is suitable for transmitting weak signals, and silicon steel is suitable for medium and high signals. It would be great if there was a core material that would be suitable for the entire spectrum of signals. However, in reality, the core must be selected based on the starting point of the magnetic flux increase in the weak signal region of the maximum magnetic flux density. Accordingly, permalloy and silicon steel produce different sounds.

THE SOUND OF AN IRON CORE

The lower the nickel and silicon steel content in the core, the harder the resulting sound.

Iron cores are often used in transformers. Since audio transformers have windings with a large number of turns, it can be said that the signal in the high-frequency range is transmitted almost directly, even if there was no core at all. Specific problems of transformers begin to appear when it becomes necessary to transmit signals in the mid- and low-frequency range. The first thing they look at when evaluating the properties of an iron core is the hysteresis loop. However, this is only an approximate characteristic, since windings will be added later, and this will be a different system. The second step is to determine what magnetic flux the core can pass and where the saturation point is. This is quite sufficient for a power transformer, but further research is needed for audio transformers. The fact is that when calculating power transformers, the features of transmitting weak pulse signals are not considered. To transmit such signals, the core must react sensitively even to a very weak magnetic field. For this purpose, a so-called nickel core is usually used, containing from 45% to 78% nickel. The problem with the nickel core is the low maximum magnetic flux density. There are many different types of nickel cores, each sounding differently, but in general it can be said that the lower the nickel content, the harder the resulting sound. On the other hand, when silicon steel is used in the output transformer, there is a tendency to soften the sound, smoothing out the boundaries and transitions, since no magnetic flux occurs in the region of weak signals.

TRANSFORMER AND SILVER WIRE

The core roughens the sound of the inductor coil if the coil is wound with copper wire.

Among the many factors that affect the sound quality of a transformer, one of the most important is the material of the winding. If we compare the sound of the output transformers of a single-ended and a push-pull amplifier, the former will have a cleaner signal envelope. Considering the various causes of this phenomenon, I highlight one that no one has paid attention to yet. I mean the presence or absence of a constant magnetic field that occurs when direct current flows through the winding in a single-ended and push-pull amplifier, respectively. I think this magnetic field can enhance the manifestation of differences in the sound of windings made of different materials. In other words, we are talking about the relationship between the additional magnetic field and the behaviour of electrons. Experiments show that if you wind coils around an ordinary horseshoe magnet and send a sound signal, the degree of change in sound quality due to the difference in wire material will be greater than without a magnet. Numerous experiments have shown that when using silver wire for winding, the sound undergoes only minor changes in the presence and absence of an additional magnetic field. Copper wire changes the sound towards a “rough” sound. If you use silver wire in a regular transformer, its sound will change radically. Now it becomes clear that the claims that the transformer allegedly spoils the sound are simply groundless. And this fact cannot be denied only because the theory of electricity still cannot reliably explain the essence of the relationship between the magnetic field and silver. Sooner or later, people will honestly admit this objective reality. In conclusion, I will only add that in its push-pull amplifiers, Audio Note Japan uses DC biasing of the output transformers.

PRE-AMPLIFIER ON HIGH-VOLTAGE FIELD-EFFECT TRANSISTORS

The M7 preamplifier uses interstage capacitors with oil-impregnated paper.

The first product of Audio Note Japan was a preamplifier in which I used high-voltage field-effect transistors developed by Mr. Shigeru Terada with the assistance of Shindengen. It should be recalled that at first, field-effect transistors were used, like vacuum tubes, as voltage-amplifying elements. But the high level of distortion did not allow their use in amplifiers claiming high quality. Field-effect transistors used instead of vacuum tubes had a volt-ampere characteristic that was unusual for semiconductors and generously generated the second harmonic. In addition, their use was complicated by the low voltage, about 50 volts, for which they were designed. But then Mr. Terada developed a field-effect transistor that could withstand 200 volts. This phenomenal improvement greatly simplified the design of amplifiers and significantly expanded the range of application in circuits with low distortion. I designed a preamplifier using such field-effect transistors, which became the prototype of the Meister-7 model, abbreviated M-7. The case was quite large, in its upper part there were oil and electrolytic capacitors of the power supply. Later I made a more compact M-7II, in which I used a cascode circuit for the amplifier stage. The advantage of such a circuit was that it significantly reduced leakage current and distortion at the same time. At that time I also used interstage capacitors with oil-impregnated paper. After the cessation of production of field-effect transistors developed by Mr. Terada, I stopped assembling the M-7. Only 100 preamplifiers of this model were produced. I heard that some copies still work and are highly valued.

ON GAKU AMPLIFIER

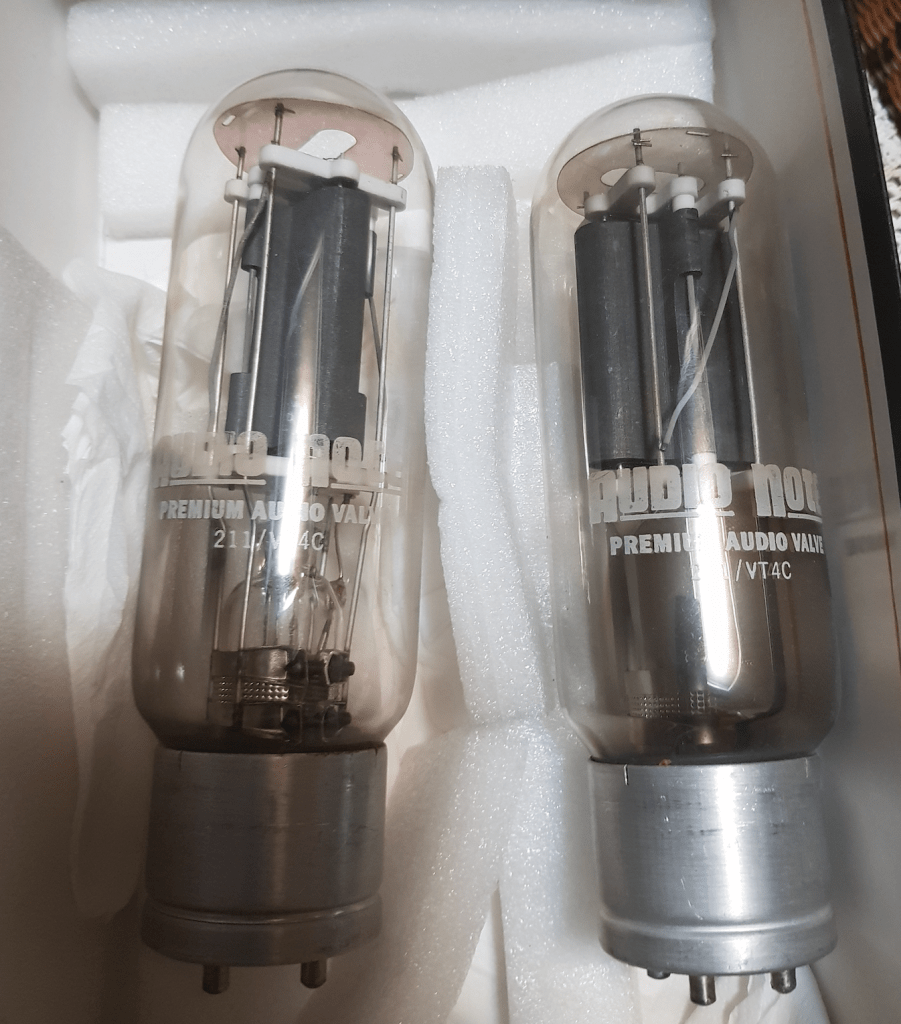

The On Gaku’s captivating sound is the result of high voltage 211 tubes, silver wires, silver foil capacitors and silicon steel cores.

What is the phenomenon of the attractiveness of the sound of a tube amplifier? One of the factors, from the point of view of circuit engineering, is the ability of the tubes to work with high voltage. For example, among the tubes presented today, the 211 “holds” more than 1000 volts. The 211 has a large-mesh grid and, thanks to the low bias voltage, the number of electrons that do not reach the anode is extremely small, which means excellent linearity of the volt-ampere characteristic. With a gain of m = 4, it is almost ideal. Many people think that using such an outstanding element, creating an amplifier with good characteristics is not difficult. I made several amplifiers on 211-S triodes, but none of them satisfied me with the quality of their sound, despite the excellent electrical characteristics that measurements showed. They lacked the tenderness of 2A3 and the depth of 300V. After a series of trials and errors, I came to the conclusion that the problem lay in the sound quality of the components used in combination with this tube, since the 211 itself was beyond doubt. So I turned to Mr. Yasuhiro Oishi, who helped me make silver wire windings for the silicon steel core output transformers. The result was astounding. What a fascinating sound! Inspired by this discovery, I made signal capacitors from silver foil. All this resulted in a sound that no one had managed to achieve before, and Mr. Masahiro Shibazaki of Sibatech gave this amplifier the most appropriate name at the time – Ongaku, which means Music.

TCHAIKOVSKY’S PATHETIC SYMPHONY

This piece requires sound reproduction technology that is hard to even imagine. Can an amplifier and speaker system exist that can convey all the feelings that Tchaikovsky put into this complex music?

What an inner strength this melody has! The sudden change of mood after the second theme of the first movement is disconcerting. I tried to interpret this piece in my own way. A young man, overcome with excitement, begins his life’s journey, turning to the unknown. At the edge of his abilities, he fights with the world around him and with himself. A bright ray of luck saves him and he wins. But time is inexorable, it does not allow even a fleeting respite after the battle. Now he must confront the underground spirits. The thunderous peals of the timpani paralyse the listener with horror. But reconciliation comes and with a deep sigh he calmly plunges into sleep. This symphony is full of unusual orchestrations. Brass instruments follow the bass register of the woodwinds. Everything is permeated with the low sound of the strings. Thunderous fortissimo gives way to unreal pianissimo. The constant alternation of retardando and accelerando keeps you on edge. This piece demands the highest performing skills from the musicians, and from the audio equipment – reproduction technology that is hard to even imagine. I am trying to understand whether there can be an amplifier and loudspeakers capable of conveying all the feelings that Tchaikovsky put into this most complex music. I am sure that today my amplifiers, loudspeakers and magnetic heads can convey the subtlest shades of music to the listener more deeply and honestly than any other equipment, the sound of which sometimes resembles a senseless pile of sounds. My equipment will not yield to any compromises.

211 AND 300B

It was Japanese audiophiles who revealed to the world the unique sound of the 300B, the secret of which lies in the special suspension of the filament, which introduces reverberation into the sound of the tube.

The 300B and 211 are comparable in sound. Both are American inventions from the days when that country had not yet lost its enthusiasm for producing quality consumer goods. In a sense, the 300B is easier to use, since it only requires 400 volts of plate voltage. I dare say that it was Japanese audiophiles who introduced the world to the superb and unique sound of the 300B. If you have ever made or listened to a 300B amplifier, you know what I mean. The secret is said to be in the design of the filament suspension. It hangs down, supported by springs. If you remember, the first mechanical reverberators were also spring-type. In a sense, a microscopic echo machine was placed inside the vacuum tube. This is partly confirmed by the quiet echo produced by tapping the 300B bulb. The difference in the sound of the 211 and 300B is due to the materials from which their direct heating cathodes are made. For strengthening, the filament of the 211 contains thorium. Do not forget that these tubes were intended for use in military equipment. The amplifier on 211 triodes sounds clear and dense. I would like to note that the 300B Golden Dragon has excellent characteristics. I say this with special pride, because these tubes use tungsten made using the most advanced Japanese technology.

LONG-PLAYING RECORDS

Who knows, maybe large long-playing records will once again be resurrected as the main carrier of musical information.

Long-playing records (LPs) were invented around 1949, at the same time that tape recorders began to be used for radio broadcasts. Experiments with stereo recording began around 1955. The first half of the 1950s were marked by stunning innovations in the music world, as well as a huge breakthrough in the quality of sound reproduction. In particular, the emergence of the LP can be compared in its significance to Edison’s invention of the wax cylinder phonograph. LPs were born in the bowels of CBS laboratories thanks to Peter Goldman (the golden man!) and the efforts of other engineers. When I visited CBS in 1970, I was proudly shown the first machine for cutting LP masters. In essence, it was an improved lathe, so it was called a “LATHER”. CBS shared the invention with its competitor RCA. Both companies were world leaders in recorded music at the time. Mr. David Sarnoff, then president of RCA, in turn, immediately tasked his engineers with developing a compact and lightweight disc, which led to the birth of the EP. As a result, a natural division of roles developed – LPs were used for recording long-playing music, such as classical music, and EPs were used mainly for popular music. I hope readers can imagine the socio-cultural background of this phenomenal era. History repeats itself, and who knows, maybe the big long-playing records will once again be resurrected as the main carrier of musical information…

TOSCANINI

RCA recorded the orchestra under the maestro with superb clarity of sound, but without natural reverberation.

“As the Führer of the Third Reich, I have a burning desire to attend your performance…” – “My music is not for Satan.” These words are from the correspondence – a humble letter from Hitler to Maestro Toscanini and the latter’s reply. In the 1930s, the world was bent under many problems, and the ESB – Empire State Building was just about to get rid of the shameful nickname of the Empty State Building.

Italians certainly have a love of debate on any occasion. Walking through Milan in the evening, you can see curious scenes: here and there people gather in groups and argue excitedly… But in those difficult times we are talking about, Toscanini did not cease to fearlessly speak out for democracy. Albert Einstein would later say: “You are not only the world’s greatest conductor – by fighting fascism, you have proven the nobility of your character.” Toscanini left a historical mark on the life of the European musical community of the 1930s. In January 1937, he was forced to make a difficult decision – to go to America and work exclusively for American radio broadcasting.

When I was looking at a recently purchased Toscanini CD, my attention was drawn to the mention of Socony Oil Company as a sponsor. Toscanini was already planning to retire and went to America with extreme reluctance. Therefore, the Americans, when receiving him, tried to provide the most favourable conditions. For RCA, with its money, it was not difficult to assemble a world-class orchestra especially for the Great Maestro. Socony Oil Company became a sponsor for the newly formed orchestra. It should not be forgotten that America’s prosperity was ensured, among other things, by its unlimited natural underground resources. So it can be considered a great fortune that this contributed to the preservation of a priceless musical heritage. Around the same time, an American engineer, Edwin H. Armstrong, made a landmark invention, the superheterodyne receiver. The new radio receiver allowed a huge step forward in the quality of the sound of the received broadcasts, but it was still not good enough. At that time, magnetised loudspeakers were mainly used. RCA spent a lot of effort to ensure that Toscanini’s performances were best reproduced by these loudspeakers, and the result was the appearance of the notorious “Studio 8H”. In it, reverberation was reduced to a minimum. If you listen to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony performed by Toscanini, you will notice that each of the instruments sounds very clear. However, it immediately becomes clear that the recording was made in a muffled studio.

To this day, at the entrance to Studio 8H, there is a memorial plaque in honour of the Great Maestro.

RIBBON MICROPHONES IN TOSCANINI RECORDINGS

The ribbon microphone has a frequency range that only reaches up to 7 kHz, but it still records bass strings and percussion instruments perfectly.

From a modern perspective, the ribbon microphone setup of the 8H studio looks strange. There are only three microphones arranged horizontally at the top of the studio – the main one in the centre, a backup on the right, and one more – for the high-frequency range – on the left. All microphones are made by RCA. Ribbon microphones are still used today, for example in amplitude-modulated radio broadcasting, because they are best suited for clear and intelligible voice recording. The design of the ribbon microphone is such that the ultra-light diaphragm is suspended in a strong magnetic field. It easily follows the vibrations of the air, like willow leaves rustling in the wind. The problem is that such a light diaphragm is also very soft, as a result of which it has too low a resonant frequency and, accordingly, there is a rise in the low-frequency range. In addition, the ribbon microphone does not respond to sound vibrations in the horizontal direction. This explains the specific tonal balance of Toscanini’s recordings. He used to place the first violins on the left side of the stage and the second on the right, which allowed the concert hall to achieve a large-scale sound of the string instruments and an overall harmonic balance. However, microphones with a figure-eight sensitivity pattern were not effective enough in this case, and perhaps that is why they were placed almost close to the ceiling. The ribbon microphone has a frequency range reaching only up to 7 kHz, cutting off the higher frequencies that carry a lot of emotional information. Nevertheless, it perfectly records the sound of bass strings and percussion instruments.

Hiroyasu Kondo, Audio Note Japan, June 14, 1999.

You must be logged in to post a comment.