Simon Brown, the erudite designer of the Wand tonearm, recommended that I read Daniel Levitin’s This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession. I trusted his suggestion, and it turned out to be one of those books that reshapes how you think about something you thought you already knew.

Dr. Daniel Levitin is both musician and scientist. Before becoming a cognitive psychologist and neuroscientist, he spent a decade as a musician, recording engineer, and producer. That dual background gives his book a unique voice, equally comfortable explaining a bassline or a brain scan. He manages to make the science accessible even for those without a musical background. He begins by laying out the basic terminology, and then builds layer upon layer, showing how rhythm, pitch, and timbre connect with memory, culture, and emotion. The result is a book that makes you think about all music differently: the songs you love, the songs you dislike, even the muzak playing on your lift ride from the top floor.

I came to it with my own history. I’ve played in bands, recorded music, and I still pick up the guitar every day. Yet I’ve never considered myself a ‘Musician’ with a capital M. Reading Levitin reminded me that the brain doesn’t care about that distinction. Whether you’re a professional player or someone strumming in the living room, your neural circuitry lights up the same way. The act of making or listening to music is always real, always meaningful.

Levitin makes it clear that our sense of what music “should” sound like isn’t hardwired, it’s learned. From early childhood, we absorb the rhythms, chords, and structures of our culture. By around age five, most of us already know what’s musically “legal” within that framework. That schema is constantly reshaped by what we hear and who we are with. This explains why the music of adolescence sticks so deeply: our teenage years are a time of discovery, and the songs we latch onto then fuse with memory and identity.

But familiarity alone doesn’t explain why music moves us. The real magic is in prediction. The brain is constantly guessing what comes next. When music fulfills those guesses, we feel satisfaction; when it disrupts them artfully, we feel surprise and pleasure. Miles Davis knew this. He famously said the most important part of his music was the space between the notes, especially clear on Kind of Blue. That space creates anticipation, which pulls us deeper into the sound. Great music balances the comfort of the expected with the thrill of the unexpected.

Another striking example is Stevie Wonder’s Superstition. The hi-hat alone, never quite repeating, breathes like a living thing. Levitin uses examples like this to show that we don’t just hear songs as blocks of sound, we respond to micro-variations in timing, tone, and dynamics. Our brains crave nuance. It’s why a live drummer feels alive in a way a drum machine rarely can.

The book also reveals how much of what we hear is constructed in the mind. Sound waves themselves have no pitch, they are just vibrations in the air. Pitch only exists because the brain interprets those vibrations as something meaningful. A tree falling in the woods really does make no sound unless there is a brain to hear it. Similarly, cultural context shapes our perception. Major chords are not universally “happy,” nor are minor chords universally “sad.” These associations are learned.

Levitin also highlights how timbre, the quality of sound, defines our experience more than pitch alone. A piano, a voice, and a synthesizer can all play Middle C, yet each carries a different texture. Across history, it’s timbre that has evolved most, shaping how each generation hears and feels music.

The science gets even more fascinating when Levitin turns to memory and emotion. Studies show that people often recall songs at the correct pitch and tempo without prompts, suggesting how deeply recordings imprint themselves. The cerebellum, once thought to be only about movement, also lights up in response to music we love, suggesting a primal link between rhythm and feeling. The amygdala, a key emotional center, forges powerful bonds to the music we encounter in our teens, which helps explain why those songs continue to hit us decades later.

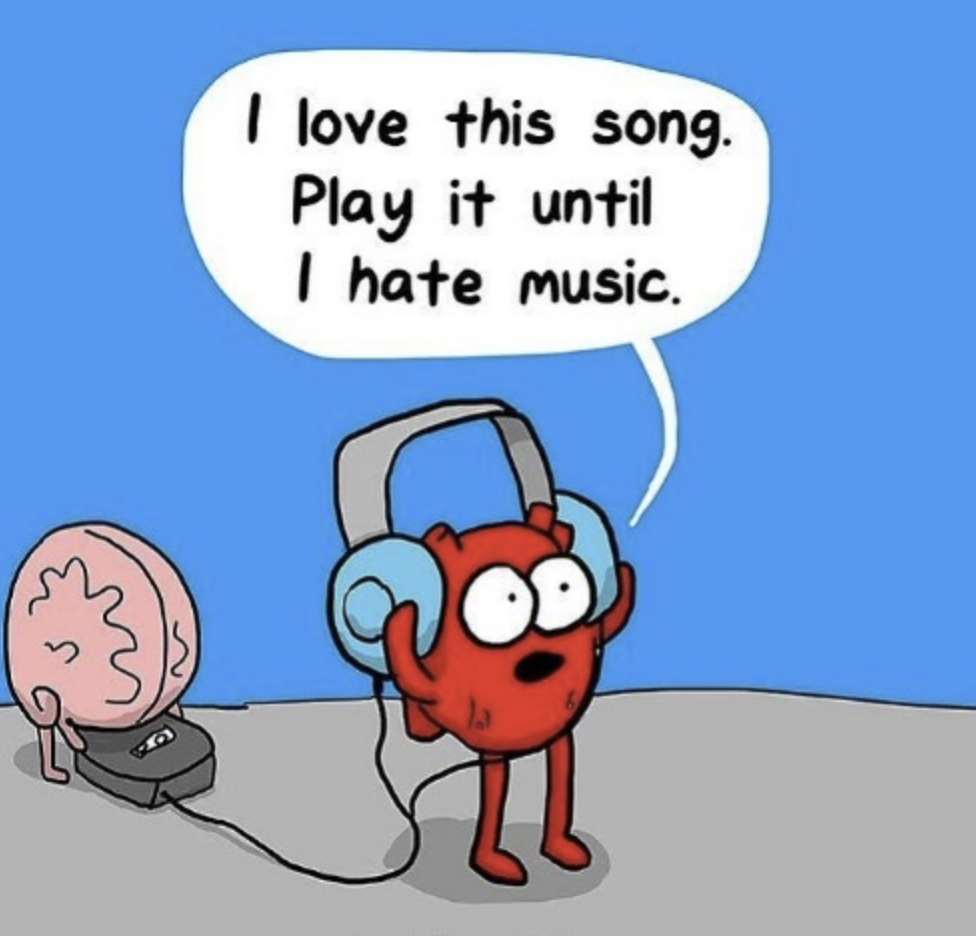

Underlying it all is a balance between simplicity and complexity. Music that is too predictable bores us, music that is too dissonant or chaotic leaves us cold (well, some people anyway, I enjoy a bit of chaotic dissonance now and then). Enjoyment lives on the inverted U-curve: enough pattern to provide anchors, enough surprise to keep us intrigued. This balance varies for each person, but it explains why some listeners gravitate to minimalism and others to jazz improvisation, both are seeking their own sweet spot between familiarity and challenge.

Levitin also challenges the idea of “talent” as a rare gift. Like language, music is something most of us are wired for. Skill comes from practice and exposure, not magic. He points to the “10,000 hours” of deliberate effort often required for mastery. The difference between obscurity and expertise, he argues, is persistence. I’ve seen this myself in both music and sport, the hours you put in matter more than the myth of talent.

And then there is vulnerability. To listen to music is to let the artist inside. That trust only works because the performer takes a risk first, exposing something of themselves. It’s why a fragile vocal delivery or a raw guitar solo can stop us in our tracks, they carry the sense that the artist has risked something real, and in turn, we risk being moved.

For me, Levitin’s book reframes the role of the audiophile. Our obsession with gear, tonearms, cartridges, cables, isn’t trivial, but it is secondary. The equipment matters only insofar as it lets the subtleties through: the breaths between notes, the shifts in tone, the details that make music feel alive. High fidelity isn’t about specs, it’s about giving the brain the raw material it needs to experience those dialogues between expectation and surprise, control and release.

Simon was right. This Is Your Brain on Music isn’t just a book about science. It’s a book about why music matters, why we listen, why we play, why we keep seeking out music. It affirms that the hours spent in bands, the daily habit of picking up the guitar, and even the tinkering with hi-fi gear are all part of something fundamental. Music is not decoration. It’s part of being human. This Is Your Brain on Music is more than a book about sound, it’s a book about what it means to be human.

You must be logged in to post a comment.