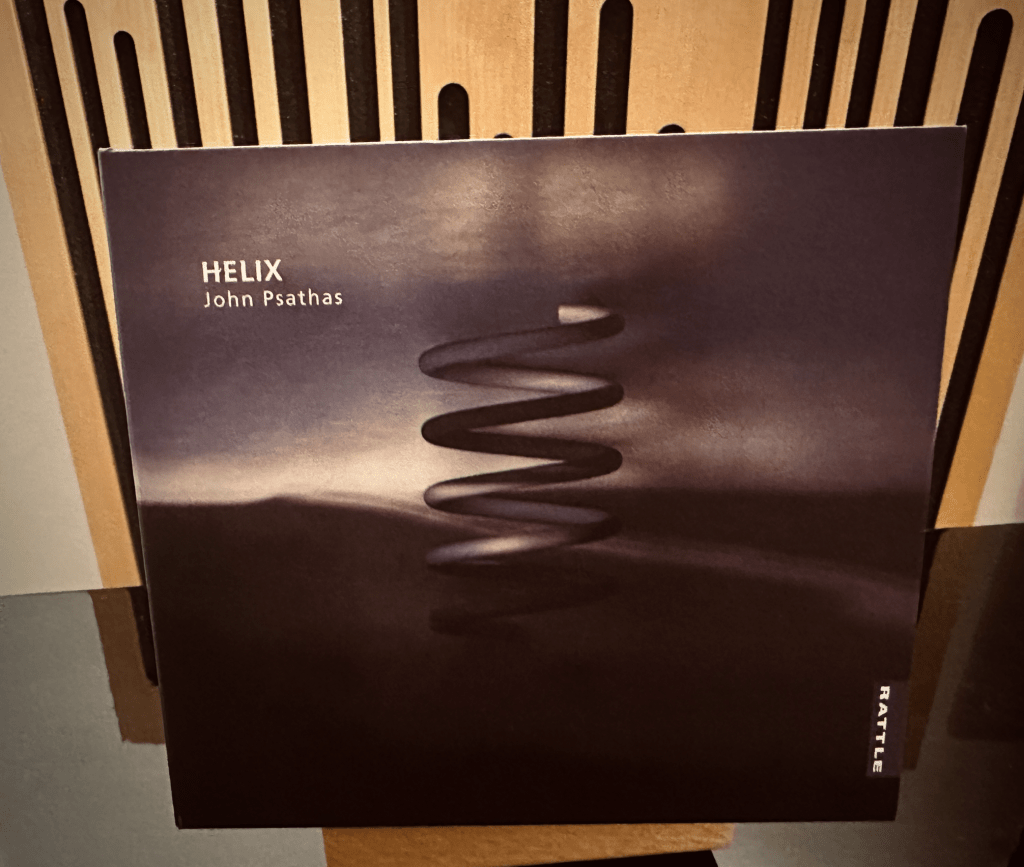

A rare trip into the city for my niece’s birthday extravaganza ended up taking an unexpected turn toward nostalgia. After lunch at a great taco place in Elliot Stables (Taco Amaiz) we meandered down Queen Street into the slowly emptying corridor of the Queen’s Arcade, and I saw that Marbecks, that long-surviving temple of CDs and vinyl, was in the final days of its closing-down sale. Fifty percent off everything. The racks were half bare, but in among the leftovers I found a copy of John Psathas’ Helix, a disc I’d never heard despite knowing his music for years. It felt like a small piece of New Zealand musical history that shouldn’t be left behind, so I bought it, went home, and put it in the ‘to listen’ pile. I finally got the chance to have a good listen the other night and it did not disappoint. I’ve been listening to a lot of vinyl lately when I’ve had the time to listen, so using the cd player was a bit of a novelty.

When Helix first appeared on Rattle Records in 2011, it marked a decisive pivot in John Psathas’ career. Having scaled the global stage with View from Olympus and the music for the 2004 Athens Olympic Games, Psathas had already established himself as New Zealand’s foremost composer of international stature, a figure whose sound world fused the drive of rock and jazz with the discipline of classical form. With Helix, he turned inward, writing for smaller forces without losing any of the scope, rhythmic intensity, or cross-cultural dialogue that defines his music.

At the heart of the album is the piano trio Helix, commissioned by NZTrio in 2006 and performed by the ensemble’s original lineup of Justine Cormack, Ashley Brown, and Sarah Watkins. Their performance was described by New Zealand Herald critic William Dart as one that “guarantees goosebumps,” earning the album a five-star rating. The work itself encapsulates Psathas’ compositional ethos: rhythm as structure, history as continuum. Across its three movements he threads the rhythmic elasticity of ancient Mediterranean dance, the harmonic brightness of 18th-century Italy, and the pulse of contemporary London club culture into a single spiralling line that gives the work its name.

Psathas has said he “went to quite a far place in terms of rhythm” when writing the trio. His studies of Bulgarian, Greek, Turkish, and Egyptian folk idioms revealed how phrasing itself breathes, accelerating into the centre of a gesture and relaxing outward. Translating that human quality into Western notation became both challenge and triumph, yielding music that feels at once ancient and futuristic. In the final Tarantismo movement, this research comes alive in ecstatic propulsion. Harmonic modulations by thirds spin the listener through tonal space while the trio drives forward with ritual intensity. The effect is electrifying.

The album opens with Songs for Simon, a four-part piano suite performed by Donald Nicolson, who also shares production and editing duties with Psathas. Here the composer’s fascination with electronics takes the foreground. Nicolson’s piano lines, sometimes crystalline and sometimes percussive, are shadowed by loops, sequences, and gamelan textures. The result is both earthy and ethereal, a dialogue between pulse and resonance that bridges acoustic tradition and digital immediacy. Demonic Thesis pushes toward chamber techno, while His Second Time recalls the atmospheric poise of ECM-era jazz.

The New Zealand String Quartet appears next in Psathas’ arrangement of Kartsigar by Greek clarinettist and composer Manos Achalinotopoulos, a nod to Psathas’ Greek heritage and an act of cultural kinship. The piece dances between hypnotic modality and taut rhythmic precision, its two sections moving from meditative chant to impassioned drive.

Nicolson returns for Sleeper, a solo piano work of introspective calm. Its minimalist clarity recalls the early glassy landscapes of Philip Glass, though Psathas’ harmonic language remains warmer and more human.

The album closes with Waiting: Still, a tribute to Psathas’ mentor and friend Jack Body. Nicolson’s spare piano gestures are set against Psathas’ gamelan textures to create a sound that feels both weightless and grounded. The piece fades to silence leaving the listener suspended, wanting more.

In retrospect, Helix stands as a hinge in Psathas’ career. The cosmopolitan voice he forged through large-scale orchestral works finds a new intimacy in chamber form. Where View from Olympus was panoramic, Helix is cellular. Yet the same energy remains: the physical propulsion of rhythm, the fusion of intellect and emotion, and the sense that every note connects past and future.

Helix is chamber music that feels alive, searching, and contemporary. It looks outward and inward, reflecting the dual identity of a New Zealander with Greek roots. The result is a work of imagination, cultural curiosity, and rhythmic vitality. More than a decade after its release, Helix still sounds like the future.

The recording quality is outstanding. The engineers have captured the instruments with real presence and clarity, and the balance between detail and warmth feels just right. Through the Esoteric player into the Kondo amp and O/Bronzes, Helix sounds alive and three-dimensional. The piano has real body and weight, the strings breathe naturally, the percussion has punch and sparkle, and the electronic layers sit perfectly in space. It is one of those recordings that makes you stop and just listen, each track revealing a little more each time.

When the final notes of Waiting: Still faded, I found myself thinking about that nearly empty shop and the slow disappearance of places like it. Marbecks might be closing, but finding this album there felt like a kind of continuity, a reminder that even as things fade, the music remains, spiralling forward like Psathas’ own helix through time. I think I’ll have to make another trip before the sale ends and see what other Psathas albums I can find, while there’s still a few days, and a few treasures left on the shelves.

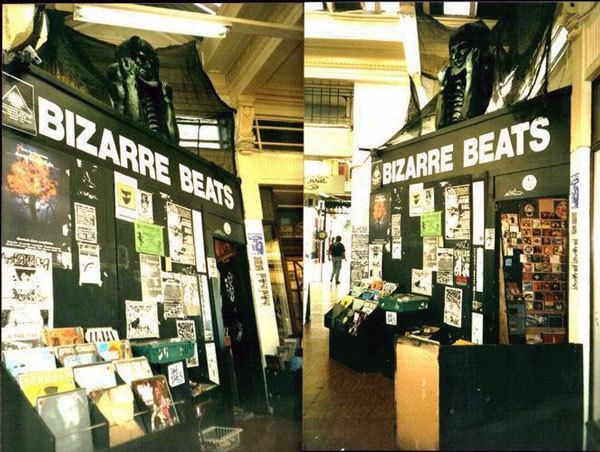

Standing there in Marbecks, I couldn’t help thinking back to when the city was full of record shops. In the 1990s, when I was at university, you could spend an entire day wandering between them; Real Groovy, Beautiful Music, Revival Records, Bizarre Beats, and half a dozen others whose names have faded but whose smell of cardboard sleeves and plastic wrap I still remember. Back then, I was almost guaranteed to run into someone I knew, and it actually happened this time too, bumping into a couple of good friends who were doing the same as me, browsing the nearly empty racks. Each place had its own mood, its own regulars, and you always left with something unexpected. Those days are long gone, but finding Helix on the shelf felt like a small echo of that time, a reminder of how music used to find you, rather than the other way around. At least Marbecks aren’t completely disappearing, and are just moving online, but, it’s not the same…

You must be logged in to post a comment.