There are albums you respect, there are albums you return to, and then there are albums that form part of your internal architecture.

In sitting down to put this together, something became very clear very quickly: it is difficult to properly explain a thirty-year connection with an album. Any album.

If music, or film, or literature has been part of your life for that long, it stops being something you consume and becomes something that sits in your emotional landscape. Sometimes foreground. Sometimes background. Sometimes years pass without revisiting it. But it’s always there.

This is not hyperbole: it is the single most influential and important album of my life.

I was into my early teens when I first started picking through heavier forms of metal. Thrash, then death metal. Then anything heavy, strange, or vaguely transgressive. I had no map. No older sibling guiding me. No scene. Just adverts and short reviews in things like the long-defunct Terrorizer magazine, bFM’s Hard, Fast and Heavy show on a Monday night, and a willingness to take risks based on little more than titles and artwork.

I had bought the first My Dying Bride EP Symphonaire Infernus et Spera Empyrium because the name was catchy and the artwork was supremely cool to my gothic/steampunk addled youthful brain.

That EP proved languid, gothic, experimental and heavy as fuck. It had violin. Violin! The idea that the instrument could live inside something this heavy, this mournful, was revelatory. When the debut album was released, As the Flower Withers, I was already a convert. The next EP was The Thrash of Naked Limbs, and it is still one of my favourite releases to this day, but nothing could have prepared me for the magnificence that was to come in the form of the second album, Turn Loose the Swans. The title was so weird and strange. Everything about this band was enigmatic… they only used their first names on releases. They were a mystery. It was just cool.

I remember another moment clearly: buying the album at Real Groovy Records, bringing it home, putting it on immediately, and sitting on my bed eating chocolate dipped strawberries while it played. I had prepared them as I knew it would be an event. The sweetness against that immense, gothic melancholy. It shouldn’t make sense. But that’s how memory works. The album fused with a sensory moment and lodged itself permanently.

Recorded at Academy Studios and produced by Mags, Turn Loose the Swans is not a pristine recording in the modern sense. It is far better than that.

The guitars are thick but slightly grained, not razor-etched. There’s a fog around the edges. The drums breathe; the room is audible. No triggered sterility. The kick drum has weight without annoying clickyness. The snare has wood in it. The toms sound like toms.

If your stereo preserves harmonic layering and texture, the record opens like a damp stone ruin and reveals its gothic medieval depth and hidden detail. This is an album that lives in the midrange. If your system compresses that band, you lose the emotional information.

The violin is not decorative, it is a structural element. Often forward in the mix, sometimes weaving beneath the guitars, it gives the record that unmistakable gothic medieval feel. Not cheesy theatrical gothic, nor lame-ass Halloween gothic. Something older. Processional maybe, bordering on liturgical.

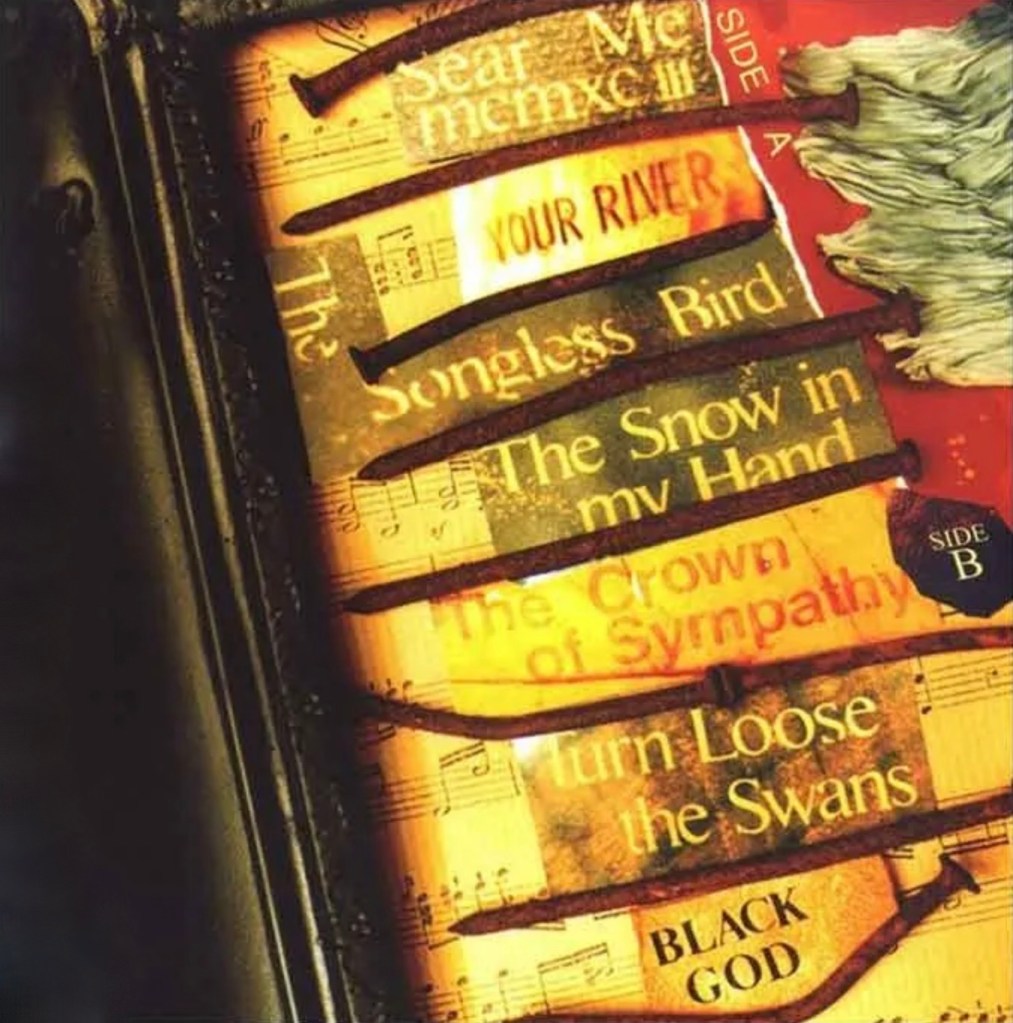

Sear Me MCMXCIII

For a teenager expecting death metal, this opener was bewildering. No guitars, no drums, no growls.

Bookended in spirit by the closing track, it is stripped down and stark. Clean vocals dominate, but Aaron intones rather than belts. It is ominous and strangely uplifting at once. Dark Romanticism announces itself immediately.

This is atmosphere as architecture.

Your River

The restrained opening continues before the full band arrives, including Martin Powell’s violin, establishing the album’s rise-and-fall dynamic character.

The contrast between growled verses and clean refrains is devastating. The track swells and recedes like breath. On a resolving system, the interplay between guitar harmonies and violin lines becomes deeply textured rather than dense.

“We gather thorns for flowers…”

It’s an invocation.

The Songless Bird

Perhaps one of the more “accessible” metal tracks here, though ferocious compared to what precedes it.

The lyrics shift from reverence toward something more scornful. Yet even here, the band allows sombre, harmonised passages to interrupt aggression. That dynamic control would become a hallmark of their sound.

The Snow in My Hand

Beautiful and plaintive.

The guitars feel almost anatomic, supporting the weight of the melody. There’s a fragility in the pacing. It never feels rushed. The medieval aura deepens; the chordal movement feels modal, ancient. A heavy, heavy song.

“I’ve seen them, so dark. Black, and yet fine…”

The Crown of Sympathy

A force of nature.

Brooding, pleading, almost confessional, it feels narrative. There are hints of Baudelaire in its melancholy, perhaps even echoes of Angela Carter’s gothic world-building in the way romance and darkness intertwine.

The tempo shifts here are staggering. Mellifluous dirge gives way to crushing weight, then to something almost hymnal. It is ambitious and utterly controlled, a masterclass.

Turn Loose the Swans

For me, one of the greatest doom metal compositions ever written.

The opening harmony between riff and violin is simply beautiful. Yorkshire doom, if we can call it that, shares little with 70s or 80s doom; this feels like something entirely new being born.

It is heavy, yes, but equally spacious. The pauses and deviations matter. It shouldn’t quite work on paper, but it works seamlessly.

On vinyl especially, this track expands. The reverb tails breathe, the midrange opens, the low-end grounds rather than overwhelms.

Black God

A sombre epilogue.

No guitars. Mournful and prayer-like. Where The Crown of Sympathy pleads, Black God feels like final resignation.

It closes the album quietly but ambitiously, bringing it full circle.

Aaron Stainthorpe’s vocals alternate between cavernous growls and fragile, almost wounded clean passages, which feel more intoned than actually sung, which was vaguely shocking at the time. To use clean vocals in death metal was just not done. The recording does not smooth the edges. When he shifts registers, you feel it. There is vulnerability in the clean vocals that a modern hyper-polished production might sand away. Some of it feels like a sermon.

A lot of bands adopt gothic aesthetics, but few really inhabit them.

The chord structures here often feel modal, leaning into tonalities that evoke something pre-modern. The pacing is processional. The violin lines feel almost liturgical at times. There’s a medieval solemnity that runs through the entire album, not as pastiche but as instinct.

It feels like stone corridors, damp air, candle smoke, black fabric absorbing light, feasts, and stories.

It doesn’t feel theatrical, it feels lived in.

The CD, the tape, and the LP each had different artwork variations to make each feel distinct. Of course I collected them all. Aaron has subsequently said that it wasn’t a cynical marketing ploy to sell more records, more a way of being a bit unique in the landscape. The album was more than music; it was object, artefact, and a physical extension of mood.

Holding the tape felt different to holding the CD. The LP artwork had scale. Dave McKean has always been one of my favourite artists and it was he who had done the artwork for the first couple of MDB releases. Aaron obviously took cues from his style and produced all the artwork and photography for TLTS himself.

Each format became part of the ritual of listening.

Then and Now

When I first heard this album, it was through a very cheap stereo. Modest speakers. Basic electronics. Nothing remotely audiophile.

And yet, even through that system, the essence came through. The emotional message survived the hardware, it cut through the inherent but unperceived limitations.

Now, listening on the system I have today, particularly on vinyl, the album breathes in a way I couldn’t have imagined then.

The violin has rosin and wood, the guitars separate into layered strands rather than a single wall, the drum ambience becomes dimensional. Space emerges between notes. The medieval solemnity feels monumental rather than compressed.

The record feels less like a dense wall and more like a physical space you can step into.

The swells are more dimensional. The quiet passages are more delicate. The transitions carry more nuance.

But here’s the important part: the emotional impact hasn’t changed.

If anything, it has deepened. What once felt dramatic now feels mature. What was once overwhelming now feels intentional.

It still carries that damp, gothic medieval weight. It still feels like candlelight in a stone hall.

And every time I play it, some part of me is back on my bed, strawberries in hand, cheap stereo playing away, hearing something that would shape me long after the sweetness was gone.

It reconfigured a genre inside a one-hour runtime and made an art form out of melancholy.

For me, this remains the high water mark of this strain of doom metal, even as it was establishing that strain in the first place. Later albums refined, streamlined, or stabilised the sound. But Turn Loose the Swans is the boldest, the most avant-garde, the most emotionally unguarded.

I seem to have had an instinct for cool things back in my youth… I found authors Storm Constantine and Freda Warrington in the same way, instinctively knowing they were genre defining in their way. I went on to interview My Dying Bride years later, and occasionally still chat with former members of the band.

Trying to put into words what it meant to me as a teenager, and what it means now, is bittersweet. The raw, yearning intensity of that age has long since settled into something quieter. But the music retains its power, its shock, and its beauty.

I was one of the first to fall under its spell. I remain under it still. And I am deeply, genuinely grateful.

You must be logged in to post a comment.