For most listeners today, stereo is simply assumed. Two channels, two speakers and a soundstage stretched between them. Since the late 1960s, virtually all mainstream commercial releases have been produced in stereo, and in 2026 no major label issues new albums in dedicated mono mixes. Mono, for most I would think, feels like a historical footnote.

But that misses something important.

Mono is not “less than” stereo. It is different. A mono signal contains no left-right spatial information; everything is summed into a single channel. When reproduced properly, through one speaker or identically through two, mono presents a solid, centrally anchored image with no phase-derived spatial cues.

That solidity is the first benefit.

With stereo, imaging depends on channel balance, speaker placement, room symmetry, and phase integrity. Get any of that wrong and the phantom centre wavers. Mono eliminates that variable. The image is locked. The vocals sit dead centre not because your room allows it, but because they must.

Mono also concentrates energy. Because there is no lateral spread, tonal density increases. Instruments stack vertically rather than horizontally. The presentation can feel more immediate, more direct, even more powerful.

Many classic recordings from the 1950s and 1960s were mixed primarily for mono. Engineers balanced compression, EQ, and mic placement specifically for a single-channel presentation. In those cases, mono is not a compromised version, it is the intended one.

A true mono signal contains only lateral groove modulation pressed into the LP. Remove the vertical component and you remove a great deal of potential noise. Phase concerns evaporate. Coherence becomes a given rather than a goal.

There is also a technical advantage: summing to mono removes inter-channel phase anomalies. If a stereo recording has subtle phase inconsistencies between left and right, mono playback can either expose them or, in the case of dedicated mono recordings, avoid them entirely. When the source is truly mono, playback can be extraordinarily coherent.

While no new mainstream releases are issued in mono today, well none that I have noticed anyway, there remains a niche but serious interest in high-quality mono playback. Part of that interest is archival, original pressings, early jazz, early rock, classical sessions recorded with a single microphone or a simple multi-mic mono mix. Of course reissues are still being released, that Beatles Mono boxset comes to mind.

The other part is philosophical. Mono reduces the hi-fi spectacle. It shifts the emphasis from soundstage width to tone, timing, timbral colour and harmonic structure. There is nowhere for a system to hide. If the midrange is wrong, you hear it immediately

For years I had the option of engaging a mono input on my Shindo Vosne-Romanee. It was instructive. Using that option on early pressings would tighten the centre image, lower noise, and add a coherence to the presentation.

Playing mono records with a stereo cartridge works, but it is not ideal. A true mono cartridge with solely horizontal compliance, that reads only lateral groove modulation, rejecting vertical movement that can introduce noise from wear or damage.

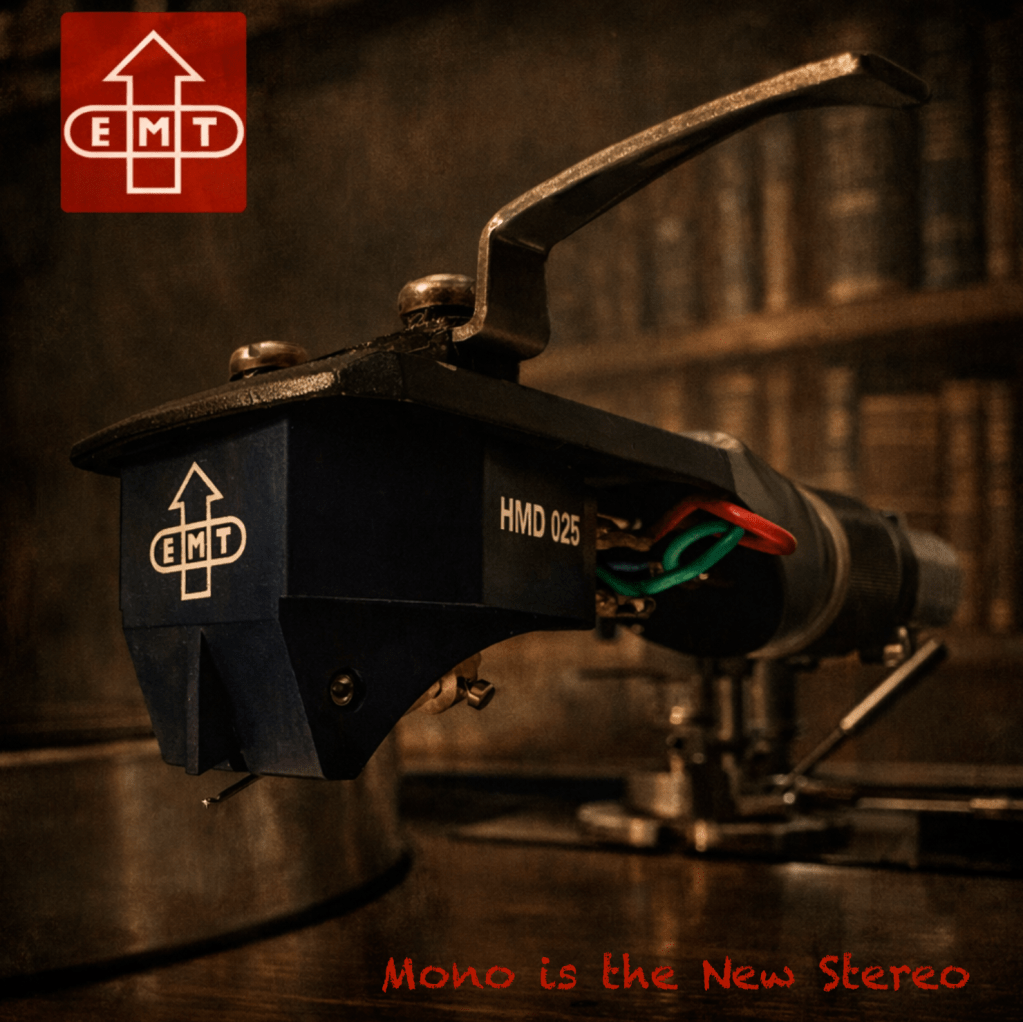

Recently I had some time to play with the EMT HMD 025, a dedicated modern mono design. What struck me was not novelty, but authority. The background was quieter. Images were carved in place with almost physical density. There was weight to instruments, a sense that the performance was being pushed forward rather than spread outward.

Alongside the HMD 025, I have also spent time with my own tondose-style EMT TMD 25 and the more accessible Ortofon 2M Mono. The EMT TMD 25 carries that classic broadcast DNA, tone that is saturated, corporeal, almost carved from oak. The Ortofon, by contrast, is leaner and more modern, but still delivers the essential mono virtues: a locked centre image and lower groove noise compared to running a stereo cartridge summed. Different price points, different flavours, but each makes the same fundamental case for dedicated mono replay.

I don’t listen to many early mono pressings anymore. My shelves hold far fewer 1950s originals than before , and I play way less jazz than in years past. Most of what I listen to now is stereo. In that context, the need for a dedicated mono cartridge becomes less urgent. The EMT is a specialist instrument. It makes complete sense if your collection demands it. If it does not, it becomes an indulgence rather than a necessity.

Stereo offers scale, space, and the illusion of depth. Mono offers focus, cohesion, and impact. The absence of new mono releases does not make the format obsolete; it simply reflects changes in production norms

For listeners willing to explore it, mono can be revelatory. It strips reproduction down to essentials. And in doing so, it reminds us that musical engagement is not dependent on width, but on substance. It’s likely if we went back to mono a lot of audiophile nonsense might disappear and listeners might focus more on the fundamentals of the performance rather than the fireworks and ‘illusory spectacular’ of modern stereo recording. This isn’t to say stereo is bad, of course it isn’t, it has huge advantages inherent in its form of presentation, just that some folks seem to think a stereo image is the be all and end of of music reproduction, and forgetting all about timbre and colour and texture.

I guess the fact that most serious cartridge manufacturers provide a mono variant shows that this sector of the market is alive and well, which is really quite cool. It would be interesting if some artists were brave enough to release modern recordings in mono and change the focus to the aforementioned tone, colour, texture and timbral cues. Unlikely though I reckon…

Audio Technica have this to say: “Generally speaking, it is possible to play a mono LP using a stereo phono cartridge, but if it is a true mono record, better performance can be obtained by using a true mono cartridge. So, what defines a true mono record? Vinyl records can be either mono or stereo and each differs greatly in the way that it is recorded and cut. Cutting refers to the mechanical process of imprinting the recorded signal into the record surface. A heated cutting stylus literally cuts the signal into the soft surface of a lacquer-coated blank disc from which vinyl copies will ultimately be made. True mono records are cut laterally: The cutting stylus moves from side to side, cutting the same signal in both record groove walls. We refer to this as horizontal modulation. The playback stylus, therefore, requires compliance (movement) in the horizontal direction only. By contrast, stereo records are cut in both lateral and vertical directions. The cutting stylus moves not only from side to side but up and down as well, therefore the stereo playback stylus requires compliance in both directions.

A stereo cartridge will never quite faithfully reproduce the true mono signal accurately because it is not restricted to horizontal compliance only. Some phase and tracking errors will exist. Additionally, there will be some amount of cross talk between the cartridge’s independent left and right channels. A true mono cartridge eliminates these problems by producing only one signal and distributing the signal to both channels equally; the signal appearing in the left and right channels will be identical. This arrangement produces a sound that is more focused (centred) and has more weight (punch). An additional benefit of the design is that of surface noise reduction. When the same exact signal is reproduced at the same time by two speakers, the signal-to-noise ratio is improved.”

I found a really good primer on mono here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.