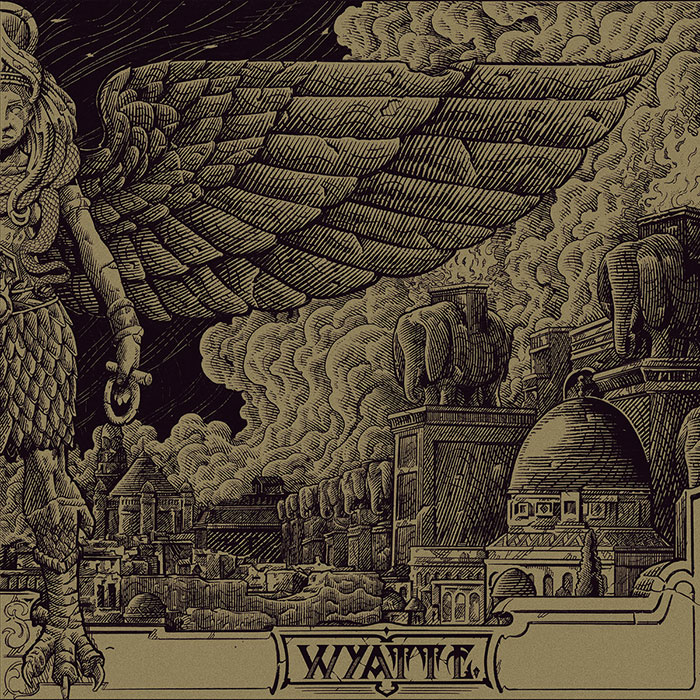

Wyatt E. – Zamāru Ultu Qereb Ziqquratu, Part 1

There must be something in the chocolate in Belgium, because a disproportionate amount of heavy, slow, and genuinely imaginative music seems to be coming out of there lately. In the space of a few weeks I’ve stumbled across two bands that feel entirely new to me yet fully formed in their own strange worlds: Wyatt E. and Briqueville. Both operate in the margins of doom, drone, and ritualistic heaviness, and both sound utterly uninterested in genre orthodoxy or trend-chasing. It reminds me why hunting for music still matters, and why certain places, for reasons that defy easy explanation, occasionally become incubators for music that feels carved rather than written.

The day after the Akitu festival is never a good time to do business. The sikaru hangs heavy, the full harvest moon still burns behind the eyes, and somewhere in the city a copper merchant is lying through his teeth while you carve a formal complaint into clay beneath a date palm. Babylon is loud, tense, ceremonial, and rotten at the edges. This is the mental state Wyatt E. want you in when Zamāru Ultu Qereb Ziqquratu, Part 1 begins.

Wyatt E. treat ancient Mesopotamia less as a history lesson and more as an emotional landscape. Originally conceived as an instrumental drone doom project portraying the captured peoples of Jerusalem after the Babylonian Exile of 587 BCE, the band have steadily expanded both their palette and ambition. Zamāru is the most fully realised version of that vision yet. It is not an album about temples and gods in a romantic sense, but about power, ritual, oppression, and the uneasy feeling that hostile forces are always just out of sight.

At its core, Zamāru is built on a droning psychedelic rock foundation, thickened with doom metal weight and inflected with modern Near Eastern tonalities. Riffs are rarely the point. Instead, Wyatt E. work with long, ominous ideas that repeat, mutate, and slowly accumulate mass until they collapse under their own gravity. The effect is less “songwriting” and more architectural. You don’t follow melodies so much as move through spaces.

The album is framed by two long-form pieces, “Qaqqari lā Târi, Part 1” and “Ahanu Ersetum”, which function like vast stone walls holding the record together. Both begin in near-amorphous sound design: a single note, a pulse, a suggestion of rhythm. Gradually, percussion layers in, textures thicken, and eventually the music erupts into colossal passages of buzzing guitar drones, sitar, and thunderous drums. The decision to record two drummers simultaneously pays off enormously here. When Jonas Sanders and Gil Chevigné lock into the same pattern, the music becomes seismic; when one holds a steady ritualistic beat while the other splinters into fills and crashes, the sense of scale and menace multiplies.

These longer tracks are immersive and undeniably effective, though they occasionally test the listener’s patience. The climaxes hit hard, but the journey toward them can feel slightly unfocused, as if a minute or two of atmosphere could have been sacrificed without diminishing the impact. In a style where the payoff is inseparable from the buildup, clarity of direction matters. Wyatt E. are close here, but not always surgical.

Where Zamāru truly excels is in its more concise middle section. The shorter tracks feel sharper, more intentional, and more memorable, committing fully to atmosphere while retaining a strong sense of identity. “Kerretu Mahrû” is a brief but intoxicating whirlwind of Middle Eastern instrumentation and intricate percussion, ending almost cruelly soon. “Im Lelya” opens with hypnotic, gently pulsing rhythms before escalating into thick, fuzzy doom, anchored by a stunning guest vocal performance from Tomer Damsky. Her voice floats and coils through the track, lending it a ritualistic intimacy that the instrumental passages alone could never achieve.

“The Diviner’s Prayer to the Gods of the Night” may be the album’s emotional centrepiece. Lowen’s Nina Saeidi delivers an ancient Akkadian prayer through a distinctly modern Iranian lens, her voice rising and falling like heat shimmering over stone. Even in its quieter moments, the track never relaxes. The instrumentation remains hushed and tense, denying the listener any real comfort beneath the starlight. It is austere, foreboding, and deeply evocative, a reminder that prayer in this world is less about solace and more about survival.

Zamāru also bears the marks of Wyatt E.’s recent detours. Their work on the synth-heavy soundtrack for the film Bowling Saturne and their Roadburn collaboration with Five the Hierophant have clearly sharpened their cinematic instincts. Like Five the Hierophant, Wyatt E. rely heavily on repetition and gradual variation, but where the former lean into wild saxophone excursions, Wyatt E. ground their sound in saz, sitar, and modal melodies reminiscent of Black Aleph’s explorations. The result feels less chaotic and more oppressive, as if the music itself is enforcing a kind of order.

If there is a lingering frustration, it is that Zamāru ends just as it fully asserts itself. At around 35 minutes, the album feels deliberately incomplete, which of course it is. This is Part 1, and it wears that designation honestly. Still, when the final notes fade, there is a strong sense of wanting more, not because the ideas are underdeveloped, but because they are compelling enough to deserve further excavation.

Zamāru Ultu Qereb Ziqquratu, Part 1 is an effortlessly distinctive record in a crowded landscape of drone, doom, and psychedelic rock. Wyatt E. balance repetition with exotic colour, weight with restraint, and concept with genuine musical substance. The guest vocalists add focus and humanity, the dual drummers add scale and physical force, and the ancient setting is treated not as a gimmick but as a living, breathing world with an underbelly as dark as its temples are tall.

In a digital age overflowing with content, originality still cuts through. Wyatt E. have carved something strange, heavy, and quietly absorbing from fertile soil. By the time Zamāru ends, you may not know exactly how you arrived at its final heights, but you will almost certainly be ready to carve a few prayers or complaints of your own into stone, just in case the gods are listening.

Mostly instrumental, the record is punctuated by moments of vocal presence that arrive like shade in the desert. You pause, you breathe, and then you’re sent back out into the heat. Middle Eastern instrumentation, language, and symbolism work together to pull you decisively out of the everyday. The ordinary drudgery simply dissolves. The real world quietly switches off, replaced by an enveloping haze of otherworldly fuzz, ritual rhythm, and sandblasted imagery that flattened everything into the same ancient plane. This is the sound of a band fully settling into itself. Zamāru Ultu Qereb Ziqquratu, Part 1 feels confident, patient, and unforced, and the fact that it is only the first half of a planned double album is genuinely exciting rather than marketing fluff. If this opening chapter is any indication, the complete work will be something substantial, immersive, and rare. This is not just a record to hear, but a journey worth committing to.

For now I’ve only been living with Zamāru in its streamed form, but it already feels like the kind of record that demands physical commitment. This isn’t background music or algorithm fodder; it’s slow, immersive, and architectural, an album that makes sense as a slab of vinyl you deliberately put on, sit with, and let unfold at its own pace. An order is imminent, if only because records like this deserve to be given space, weight, and a needle rather than a scroll.

You must be logged in to post a comment.